Visions of English Freedom

Vivianne Chastain is standing outside Whitechapel Gallery, pacing back and forth, speaking rapidly into her phone and occasionally pausing to listen. The sun is hot and throwing hard shadows. Vivianne walks across the pavement, across the path of Saturday pedestrians, up to the edge of the road. She looks a little like early Jean Seberg, perhaps, short hair and Breton stripes and brief nervous youthful movements.

Today is the opening of her new show, Visions of English Freedom. She has attracted a fair amount of hostility from the tabloid press and social media by staging the show, which questions whether the English understand what freedom means at all, right in the heart of the nation’s capital.

“This is a portrait of modern England,” reads the introductory text to a short pamphlet that accompanies the exhibition. She has exempted Scotland and Wales from her scorn, describing them as being under siege by the English government. She provokes with hyperbole and uses stereotypes as battering rams. “This is a series of photographs that captures how the English regard freedom, if they recognise it at all, if they even understand what they are looking for. This is what freedom looks like to the English. Freedom seen through English eyes. If it is seen, which it is not.”

Vivianne was born in East Berlin in 1972 and confesses to being a conformist when she was younger. She claims that her father worked for the Stasi, but there is no documentary evidence of this, and it’s not clear whether she means as an officer or an informant. She talks of military salutes for schoolteachers each morning, and tears at the Friedrichstraße train station. Others doubt she has even visited the city. It’s widely believed that she was actually born and grew up in Coventry. Certainly, the abhorrence she quite often shows for England could only have been nurtured in the dreariness of the West Midlands in the 1970s. It is part of the build up to another of her shows, a period in which she mythologises herself, inventing histories and opinions and becoming an exhibit herself.

She began her self-publicity in the 1990s when she collected some of her student work together for an imitation Freeze exhibition in a disused factory in Northampton. Some fuss was made about Instant Art Shit, her update to Manzoni’s 1961 Merda d’artista, which was comprised of packets of freeze-dried excrement that could be mixed with water to create a synthetic substitute for genuine artist’s ordure. She gained some exposure, but failed to be included in the YBA frenzy, and instead disappeared to France for several years. She says she slept in the Bois de Boulogne and worked in the kitchen at La Tour d’Argent and visited the Pompidou every day, but it’s more likely she was living with her cousin Alan, who worked for Peugeot at the time and has since explained what a nuisance she was. She journeyed further south, spent some time on the Cote d’Azur and Barcelona and Madrid, which formed the subject matter for her first show on her return to England in 2000.

Nothing much seemed to have developed artistically while she was away, although she now affected the persona of an east European migrant. Her work still appeared to be an homage to her contemporaries rather than anything that attracted the interest of critics. She may well have been trying to depict landscapes inspired by the sunny climes of Southern Europe, processing the imagery through digital distortion in an effort to use the technology at hand rather than add to the impact or meaning of her work. When these collections were damned with faint praise, she disappeared again, this time to America. She was absent for two years, and on her return to London held an intimate show that seemed to be a collection of souvenirs she had picked up on her visit. There was a marked change in her style, and she seemed far more confident in herself and her work, and more politicised. Noteworthy was Jesus’ Fake Passport, which purported to be the belongings of Christ as he attempts to illegally immigrate into the US.

Since the exhibition she has gradually picked up momentum, earning some respect from critics and occasionally managing to attract the attention of the shock-fatigued media. Her last exhibition, during which she continued the persona of a midwestern pastor’s daughter that she had affected on her return from her sojourn in the States, was praised for its documentary treatment of casual workers in the service sector. A series of video installations in Knowledge Economy depicted endless data entry and call centre repetition in the modern workplace. It was during the publicity for the exhibition that her Anglophobia seemed to become more pronounced. She angrily described the English as having become fully domesticated, and unable to know anything other than enthusiastic servitude.

“The English will never revolt because they adore their enslavement. They want to be ruled, they want to be told what they cannot do. Their upbringing by strict aristocrats has ensured they are children without any sense of adventure or self-belief. They want nothing more than the safety of knowing their place.”

Vivianne is talking to one of her guests just before the gallery admits entrance to the public. She talks with a faintly European accent, and emphasises her gestures so they appear almost manic. Her guest crosses his arms across his chest and smirks.

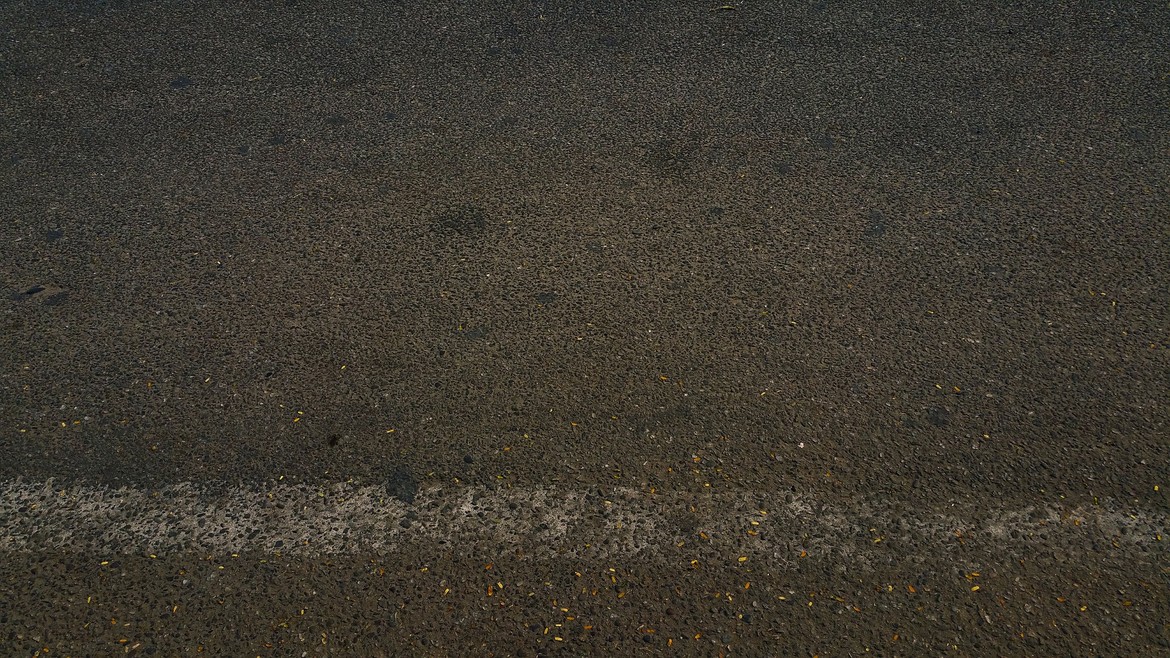

Around the walls of the gallery are hung large photographic prints of tarmac. There is little variation between the photographs. Sometimes the lines and curves of road markings, and occasional tyre skids, create shapes and interest in the images, but overall it is a grey and relentless succession of close-ups of roads.

“The English concept of freedom is tarmac, clear wide expanses of tarmac. It is perhaps not a concept of freedom, but an erstatz version, a fake that soothes, like all the other substitutes that prevent the English from actually experiencing existence. They love and hate tarmac. The English love the expanse of tarmac on which they can drive their cars, and they want to cover as much of their little country as possible with the stuff, so as to increase the expanse on which they can drive their cars. But they hate the sight of naked uncovered tarmac and want to cover it with their car wheels. See how they must drive their cars in tailbacks and ensure they cling as close to the car in front so as to keep the tarmac covered, as if to let it be seen would be to offend their indoctrinated Victorian modesty.

“The English have no control over their own lives, they have no culture or interest in ideas or any introspective ability. They wish only to isolate themselves in their cars and drive around their absurdly small and crowded island alone in their cars. It is the only freedom they are allowed to experience, which is why they adore the tarmac so much. The car is the English Id. The selfish blunt ton of steel that can communicate through one blast of a horn, that believes it has the right of way on all situations, that never doubts its own righteousness.”

Her laugh reverberates around the gallery for a few moments. It is mischievous and does not suit her latest persona. She takes the elbow of her guest and walks him across to one of the images, so they can be almost engulfed within the expanse of grey road. She has acquired a flute of champagne from somewhere.

“This is a portrait of England, the way the English want it to be. They pretend to see Englishness in the rolling hills of their postcards, but what they really want is this grey hard surface on which to manoeuvre their cars. This is not an environmental campaign at all. I have no affinity with the green movement. This is England seen through the utilitarian eyes of the English. They want only convenience for their atomised commutes. Commute to the place of work, to the out of town supermarket, to the leisure venue, back to their homes. The sight of this expanse of tarmac excites the English, makes them want to perform a pointless journey to collect an impulse buy or just avoid being with another person. Unlike citizens in other countries, the English love cars not for the transport factor but for the isolation and atomisation. This is why car shares do not work. Because the point of the car is not transportation, but isolation from others.”

They move along a row of images, made small by the wide prints, raising their hands to point out variation in the texture of the road surfaces, following the lines of paint that are occasionally included in the photographs.

“The English see the expanse of tarmac as a right, and the further covering of land with tarmac as manifest destiny. It is their right to perform their needless short journeys on this tarmac, as if they had any rights. But they are born into a country in which they have no rights. They are subjects in an oligarchy. They run their toy cars around on the ever-expanding tarmac like abused children madly forgetting the horror of their home life in a few moments of playtime. The English encase themselves in their steel boxes and see some kind of hope in the expanse of tarmac. They just want more tarmac, as if the expanse of grey itself was liberating. It represents the English birthright, the right to be able to drive on tarmac. Ask the English about politics and they will talk to you about parking spaces. Ask them about economics and they will talk to you about the price of petrol. Appeals to reason are via the motorist. New government policies are sanity checked by how they will appeal to the motorist.

“Perhaps we could date the English constitution to 1959, when the M1 motorway was opened, and English freedom was realised. The right of the English to exercise their freedom became a reality. We can understand the American fascination with the motorcar because of the size of the country and the unexplored lands and the mythology of travel. But British sit in tailbacks in sprawling grey suburbia in their own cars for no other reason than that they hate each other. They are embarrassed that they are so humiliated by the ruling classes. Self hate.

“Perhaps the English constitution is in the lines on the tarmac, perhaps this is where the non-existent document is written. It is the only regulation of life that all the English respect and observe, wherever they are in the class system. Everyone respects road markings as if they were beyond questioning. To disrespect them is to break with the social contract, to invite contempt from everyone. In no other part of the life of the English is the law and convention so respected.”

Vivianne stand in front of one of her prints, framed by the grey backdrop, the stripes of her jumper contrasting sharply. She puts down her glass and walks away from her guest, back towards the entrance of the gallery. Soon the chatter of the public begins to erode the silence. It’s difficult to know whether they will be offended by the pictures.

Subscribe to Kublic

Get the latest posts delivered right to your inbox